Understanding Stingray Surveillance Technology and its Possible Use at Recent Protests: A Guide

Since May, activists have noticed the presence of unidentified aerial vehicles hovering overhead during protests against police brutality and in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. It was later revealed that the Drug Enforcement Agency and U.S. Marshals Service were asked by the Justice Department to provide unspecified support to law enforcement during protests. A memo later obtained by BuzzFeed News revealed that the DEA had sought special authority to covertly spy on Black Lives Matter protesters using advanced surveillance technologies.

Although the exact nature of the support and surveillance was not disclosed, it is believed that the two agencies were asked to assist police in their efforts. The DEA and the Marshals both possess planes equipped with advanced surveillance technologies that can track mobile phones or collect data and communications in bulk. These technologies, known as stingrays or dirtboxes, are powerful tools that raise concerns about the potential infringement of civil liberties.

Stingrays, which have been used by law enforcement on the ground and in the air for several years, are highly controversial due to their data collection practices. These advanced surveillance technologies not only gather information from targeted phones, but also from any phone within their range. This data can be used to monitor the movements of individuals, such as protesters, during and after demonstrations, as well as to identify their associates. Additionally, stingrays have the capability to inject spying software into specific phones or direct them to malware-loaded websites, although it is unclear if any U.S. law enforcement agencies have utilized these functionalities.

Surveillance technologies like stingrays have been used by law enforcement since the 1990s, but it wasn’t until the last decade that the public became aware of their existence. However, there is still much about their capabilities that remain unknown due to the secrecy surrounding their use by law enforcement and the manufacturers of the devices. While these technologies are typically used to target suspects in criminal investigations, activists believe they have been utilized in protests against the Dakota Access pipeline and Black Lives Matter demonstrations. While federal agents are required to obtain a probable cause warrant before using these technologies in criminal cases, a national security carve-out exists. With President Trump referring to protesters as “terrorists” and the deployment of DHS officers to Portland, it is possible that the government has used stingrays without warrants to collect data on protesters. To understand the potential surveillance directed towards protesters, it is important to breakdown what is known and unknown about stingrays, and why their use is contentious.

Stingray: Definition, Characteristics and Information

A stingray, also known as a cell-site simulator or IMSI catcher, is an electronic surveillance device that mimics a cell phone tower. By doing so, it can trick mobile phones and other devices into connecting to it instead of an actual cell tower, which enables the operator of the stingray to access user and device information.

Why is the electronic surveillance tool called a stingray?

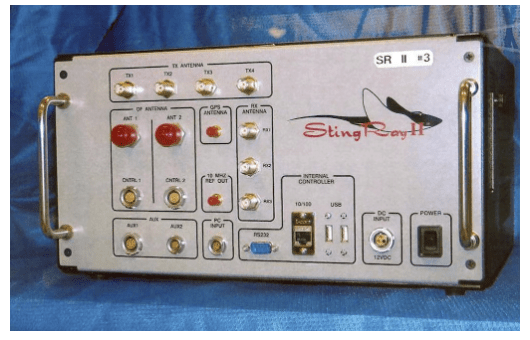

The name “stingray” originates from the Harris Corporation’s commercial model of IMSI catcher, which they branded as the StingRay. This briefcase-sized device can be operated from a vehicle while plugged into the cigarette lighter. Other companies also make variations of the stingray with different capabilities, such as Harris’ Harpoon signal booster and KingFish hand-held device. The stingray and its variants are expensive and typically sold as a package. According to Motherboard, Harris offered a KingFish package for $157,300 and a StingRay package for $148,000, excluding training and maintenance. Recent documents suggest Harris has introduced a newer model called the Crossbow, but little information is available about its workings. A classified catalog of surveillance tools leaked to The Intercept in 2015 also described similar devices.

How does the stingray work?

Phones periodically and automatically broadcast their presence to the cell tower that is nearest to them, so that the phone carrier’s network can provide them with service in that location. They do this even when the phone is not being used to make or receive a call. When a phone communicates with a cell tower, it reveals the unique ID or IMSI number (International Mobile Subscriber Identity) associated with the SIM card in the phone. The IMSI number identifies that phone and its owner as a paying customer of a cell carrier, and that number can be matched by the carrier to the owner’s name, address, and phone number.

A stingray masquerades as a cell tower in order to get phones to ping it instead of legitimate cell towers, and in doing so, reveal the phones’ IMSI numbers. In the past, it did this by emitting a signal that was stronger than the signal generated by legitimate cell towers around it. The switch to 4G networks was supposed to address this in part by adding an authentication step so that mobile phones could tell if a cell tower is legitimate. But a security researcher named Roger Piqueras Jover found that the authentication on 4G doesn’t occur until after the phone has already revealed its IMSI number, which means that stingrays can still grab this data before the phone determines it’s not communicating with an authentic cell tower and switches to one that is authenticated. That vulnerability still exists in the 5G protocol, says Jover. Though the 5G protocol offers a feature that encrypts the IMSI when it’s disclosed during pre-authentication communication, law enforcement would simply be able to ask phone carriers to decrypt it for them. And a group of researchers from Purdue University and the University of Iowa also found a way to guess an IMSI number without needing to get a carrier to decrypt it.

Because a stingray is not really a tower on the carrier’s network, calls and messages to and from a phone can’t go through while the phone is communicating with the stingray. So after the stingray captures the device’s IMSI number and location, the stingray “releases” the phone so that it can connect to a real cell tower. It can do this by broadcasting a message to that phone that effectively tells the phone to find a different tower.

IMSI Numbers: How Can Law Enforcement Use Them?

Law enforcement can use a stingray either to identify all of the phones in the vicinity of the stingray or a specific phone, even when the phones are not in use. Law enforcement can then, with a subpoena, ask a phone carrier to provide the customer name and address associated with that number or numbers. They can also obtain a historical log of all of the cell towers a phone has pinged in the recent past to track where it has been, or they can obtain the cell towers it’s pinging in real time to identify the user’s current location. By catching multiple IMSI numbers in the vicinity of a stingray, law enforcement can also potentially uncover associations between people by seeing which phones ping the same cell towers around the same time.

If law enforcement already knows the IMSI number of a specific phone and person they are trying to locate, they can program that IMSI number into the stingray and it will tell them if that phone is nearby. Law enforcement can also home in on the location of a specific phone and its user by moving the stingray around a geographical area and measuring the phone’s signal strength as it connects to the stingray. The Harris StingRay can be operated from a patrol vehicle as it drives around a neighborhood to narrow a suspect’s location to a specific cluster of homes or a building, at which point law enforcement can switch to the hand-held KingFish, which offers even more precision. For example, once law enforcement has narrowed the location of a phone and suspect to an office or apartment complex using the StingRay, they can walk through the complex and hallways using the KingFish to find the specific office or apartment where a mobile phone and its user are located.

Does the device only track mobile phones?

No. In 2008, authorities used a StingRay and a KingFish to locate a suspect who was using an air card: an internet-connectivity device that plugs into a computer and allows the user to get online through a wireless cellular network. The suspect, Daniel Rigmaiden, was an identity thief who was operating from an apartment in San Jose, California. Rigmaiden had used a stolen credit card number and a fake name and address to register his internet account with Verizon. With Verizon’s help, the FBI was able to identify him. They determined the general neighborhood in San Jose where Rigmaiden was using the air card so they could position their stingray in the area and move it around until they found the apartment building from which his signal was coming. They then walked around the apartment complex with a hand-held KingFish or similar device to pinpoint the precise apartment Rigmaiden was using.

What is a dirtbox?

A dirtbox is the common name for specific models of an IMSI catcher that are made by a Boeing subsidiary, Maryland-based Digital Receiver Technology — hence the name “DRT box.” They are reportedly used by the DEA and Marshals Service from airplanes to intercept data from mobile phones. A 2014 Wall Street Journal article revealed that the Marshals Service began using dirtboxes in Cessna airplanes in 2007. An airborne dirtbox has the ability to collect data on many more phones than a ground-based stingray; it can also move more easily and quickly over wide areas. According to the 2006 catalog of surveillance technologies leaked in 2015, models of dirtboxes described in that document can be configured to track up to 10,000 targeted IMSI numbers or phones.

Do stingrays and dirtboxes have other capabilities?

Stingrays and dirtboxes can be configured for use in either active or passive mode. In active mode, these technologies broadcast to devices and communicate with them. Passive mode involves grabbing whatever data and communication is occurring in real time across cellular networks without requiring the phone to communicate directly with the interception device. The data captured can include the IMSI number as well as text messages, email, and voice calls.

If that data or communication is encrypted, then it would be useless to anyone intercepting it if they don’t also have a way to decrypt it. Phones that are using 4G employ strong encryption. But stingrays can force phones to downgrade to 2G, a less secure protocol, and tell the phone to use either no encryption or use a weak encryption that can be cracked. They can do this because even though most people use 4G these days, there are some areas of the world where 2G networks are still common, and therefore all phones have to have the ability to communicate on those networks.

The versions of stingrays used by the military can intercept the contents of mobile communications — text messages, email, and voice calls — and decrypt some types of this mobile communication. The military also uses a jamming or denial-of-service feature that prevents adversaries from detonating bombs with a mobile phone.

In addition to collecting the IMSI number of a device and intercepting communications, military-grade IMSI catchers can also spoof text messages to a phone, according to David Burgess, a telecommunications engineer who used to work with U.S. defense contractors supporting overseas military operations. Burgess says that if the military knows the phone number and IMSI number of a target, it can use an IMSI catcher to send messages to other phones as if they are coming from the target’s phone. They can also use the IMSI catcher for a so-called man in the middle attack so that calls from one target pass through the IMSI catcher to the target phone. In this way, they can record the call in real time and potentially listen to the conversation if it is unencrypted, or if they are able to decrypt it. The military systems can also send a silent SMS message to a phone to alter its settings so that the phone will send text messages through a server the military controls instead of the mobile carrier’s server.

Can the devices be used to infect phones with malware?

Versions of the devices used by the military and intelligence agencies can potentially inject malware into targeted phones, depending on how secure the phone is. They can do this in two ways: They can either redirect the phone’s browser to a malicious web site where malware can be downloaded to the phone if the browser has a software vulnerability the attackers can exploit; or they can inject malware from the stingray directly into the baseband of the phone if the baseband software has a vulnerability. Malware injected into the baseband of a phone is harder to detect. Such malware can be used to turn the phone into a listening device to spy on conversations. Recently, Amnesty International reported on the cases of two Moroccan activists whose phones may have been targeted through such network injection attacks to install spyware made by an Israeli company.

U.S. law enforcement use of stingrays domestically is more curtailed, given that they, unlike the military, need to obtain warrants or court orders to use the devices in federal investigations. But there is little transparency or oversight around how the devices are used by federal agents and local police, so there is still a lot that is unknown: for example, whether they’ve ever been used to record the contents of mobile phone communications or to install malware on phones.

News stories suggest that some models of stingrays used by the Marshals Service can extract text messages, contacts, and photos from phones, though they don’t say how the devices do this. Documents obtained by the ACLU in 2015 also indicate such devices do have the ability to record the numbers of incoming and outgoing calls and the date, time, and duration of the calls, as well as to intercept the content of voice and text communications. But the Justice Department has long asserted publicly that the stingrays it uses domestically do not intercept the content of communications. The Justice Department has stated that the devices “may be capable of intercepting the contents of communications and, therefore, such devices must be configured to disable the interception function, unless interceptions have been authorized by a Title III [wiretapping] order.”

As for jamming communications domestically, Dakota Access pipeline protesters at Standing Rock, North Dakota, in 2016 described planes and helicopters flying overhead that they believed were using technology to jam mobile phones. Protesters described having problems such as phones crashing, livestreams being interrupted, and issues uploading videos and other posts to social media.

Why are stingrays and dirtboxes so controversial?

The devices don’t just pick up data about targeted phones. Law enforcement may be tracking a specific phone of a known suspect, but any phone in the vicinity of the stingray that is using the same cellular network as the targeted phone or device will connect to the stingray. Documents in a 2011 criminal case in Canada showed that devices used by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police had a range of a third of a mile, and in just three minutes of use, one device had intercepted 136 different phones.

Law enforcement can also use a stingray in a less targeted way to sweep up information about all nearby phones. During the time a phone is connecting to or communicating with a stingray, service is disrupted for those phones until the stingray releases them. The connection should last only as long as it takes for the phone to reveal its IMSI number to the stingray, but it’s not clear what kind of testing and oversight the Justice Department has done to ensure that the devices release phones. Stingrays are supposed to allow 911 calls to pass through to a legitimate cell tower to avoid disrupting emergency services, but other emergency calls a user may try to make while their phone is connected to a stingray will not get through until the stingray releases their phone. It’s also not clear how effective the devices are at letting 911 calls go through. The FBI and DHS have indicated that they haven’t commissioned studies to measure this, but a study conducted by federal police in Canada found that the 911 bypass didn’t always work.

Depending on how many phones are in the vicinity of a stingray, hundreds could connect to the device and potentially have service disrupted.

Rewritten: For how long has law enforcement been utilizing stingrays?

The origins of stingray technology are uncertain, but it is believed to have originated in military settings. The first public instance of a similar tool being used by U.S. law enforcement was in 1994 when the FBI used a crude version, called Triggerfish, to track former hacker Kevin Mitnick. In 2009, an FBI agent revealed in court documents that cell-site simulators had been utilized by law enforcement for over a decade, not just by the FBI but also by the Marshals Service, Secret Service, and other agencies. According to recent documents obtained by the ACLU, the Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Investigations unit has used stingrays at least 466 times in investigations between 2017 and 2019. Previously, BuzzFeed News obtained records showing that HSI had used the technology 1,885 times from 2013 to 2017.

What other issues are associated with stingray technology, beyond concerns about its potential for broad surveillance?

Aside from concerns about surveillance, the use of stingray technology is also controversial due to secrecy and lack of transparency. Law enforcement agencies and the companies that manufacture the devices have prevented the public from accessing information about the technology’s capabilities and its frequency of use in investigations. Agencies sign nondisclosure agreements with manufacturers, using them to refrain from disclosing information when journalists or others file public records requests. Agencies argue that revealing how the devices work could enable criminals to undermine them, and manufacturers cite trade secrets and proprietary information as reasons for withholding sales literature and manuals.

For years, law enforcement agencies used stingrays without obtaining a court order or warrant. Even when they did seek court approval, they often described the technology misleadingly to make it appear less invasive. They would refer to stingrays as “pen register devices” in court documents, which are passive devices that record dialed numbers from a specific phone number. They didn’t disclose that the devices force phones to connect to them, that they force other phones, not just the target device, to connect, and that they can perform additional functions beyond grabbing an IMSI number. The most significant point they withheld was that the device emits signals that can track a user and their phone’s location inside a private residence. When the FBI used a stingray to track identity thief Rigmaiden in his apartment, his attorneys prompted the Justice Department to acknowledge that it qualified as a Fourth Amendment search, requiring a warrant.

Law enforcement agents have also misled defense attorneys seeking information about how their clients were tracked, not just judges. Some court documents indicate that law enforcement officials obtained location information from a “confidential source” when, in truth, they used a stingray to track the defendant.

To combat this deception, the Justice Department implemented a new policy in 2015, requiring all federal agents involved in criminal investigations to obtain a probable cause search warrant before using a stingray. The policy also mandates that agents and prosecutors disclose to judges when a warrant is for a stingray and limit the use of its capabilities to tracking a phone’s location and logging call numbers only, without collecting the contents of communication such as text messages and emails. Additionally, the agents must delete data collected from non-targeted phones within 24 hours or 30 days, depending on the circumstances.

Law enforcement agents have also misled defense attorneys seeking information about how their clients were tracked, not just judges. Some court documents indicate that law enforcement officials obtained location information from a “confidential source” when, in truth, they used a stingray to track the defendant.

To combat this deception, the Justice Department implemented a new policy in 2015, requiring all federal agents involved in criminal investigations to obtain a probable cause search warrant before using a stingray. The policy also mandates that agents and prosecutors disclose to judges when a warrant is for a stingray and limit the use of its capabilities to tracking a phone’s location and logging call numbers only, without collecting the contents of communication such as text messages and emails. Additionally, the agents must delete data collected from non-targeted phones within 24 hours or 30 days, depending on the circumstances.